How to feel safe in your body after trauma & anxiety

Feeling unsafe in your own body can be one of the most distressing after-effects of trauma, chronic stress or long-term anxiety. Even when life around you is calm, your body may tighten, brace or stay on alert, as if something could go wrong at any moment.

This is not a personal failing or a sign that you are “overreacting.” It is a reflection of the way your nervous system has learned to protect you. Trauma does not only shape the mind; it reshapes physiology, perception and the body’s sense of what is safe.

The good news is that safety can be rebuilt. Through somatic practices, nervous-system education and gentle body-first techniques, it is possible to teach your system how to soften, settle and feel more safely at home inside yourself. In this article, we will explore what felt safety really is, how the body detects danger, why some systems stay on alert, and the somatic practices that help you reconnect with a grounded, steady sense of safety from within.

Contents

- Why safety is the foundation of all healing

- What is felt-sense safety?

- How the body detects safety (neuroception)

- Barriers to feeling safe

- Signs of safety in the body

- Practices that rebuild felt safety

- The link between safety and connection

- Creating daily safety rituals

- Somatic Self Healing and felt-safety training

- References

Why safety is the foundation of all healing

Every therapeutic, somatic or psychological process ultimately depends on one thing; your body feeling safe enough to soften, feel and connect. Healing cannot happen in a physiology that is bracing for danger. When your nervous system is in fight, flight, freeze or shutdown, its priority is survival, not growth or restoration.

Safety allows your breath to deepen, your muscles to soften, your digestion to switch on and your brain to shift from protection to presence.

What is a felt-sense of safety?

A felt-sense of safety is the experience of safety that arises from the inside, as opposed to being told we are safe. It is a body-based knowing that “in this moment, I am safe enough.” This sense of safety is created through sensations, breath, interoception and the vagus nerve, which helps regulate the autonomic nervous system.

When your vagus nerve is active, your body receives cues that support calm, connection and groundedness. Your heart rate slows, your breath deepens, your muscles release unnecessary tension and you gain more access to being able to connect with other beings. These internal shifts form the foundation of felt-sense safety and anchor your system in a physiology where healing becomes possible.

Felt-sense safety is not about eliminating all stress or discomfort but it means your body feels resourced enough to meet what is here without overwhelming you.

How the body detects safety (neuroception)

Your nervous system is constantly scanning for cues of safety and danger. This process, known as neuroception, happens beneath conscious awareness and shapes your emotions, behaviours and thoughts (Porges, 2011).

Your body reads safety through:

- tone of voice

- facial expressions

- predictability and routine

- posture and internal sensation

- environmental cues such as light, temperature and sound

In a traumatised or overwhelmed system, neuroception becomes more sensitive and more easily triggered. A harmless sound or a small demand can feel like danger. Understanding neuroception can help you see that your reactions are not weaknesses, but physiological responses designed to protect you.

Barriers to feeling safe

For many people, the challenge is not that safety is unavailable but that their system cannot feel or trust it yet. Common barriers include:

- a history of chronic stress or trauma

- growing up in unpredictable or emotionally unsafe environments

- a highly sensitive nervous system

- past experiences of not being believed, supported or soothed

- hypervigilance, dissociation or chronic muscle tension

These barriers make perfect sense when you understand what the nervous system has lived through. Your body learned to protect you in ways that were once necessary but may no longer be helpful today.

Signs of safety in the body

Signs of felt safety are subtle, physiological and deeply individual. They may include:

- deeper, slower breathing

- muscles softening without effort

- sense of warmth or grounding in the body

- steady heart rate

- clearer thinking

- ability to make eye contact

- capacity for connection and curiosity

Your system may experience safety in small pockets at first; a few seconds here, a minute there. These micro-moments matter. They are how the nervous system learns that it is safe to soften again.

If you want to explore your own unique signs of safety, you can download my free journaling workbook resource: 'Rebuilding safety' here:

In the workbook are several journaling reflections on noticing and welcoming safety. You might like to explore this reflection slowly, over a few sittings, or simply read the questions and notice what arises. There is no need to answer everything. You can write, pause, or just sense into these prompts in your body.

Practices that rebuild felt safety

Felt safety can be cultivated with simple, consistent somatic practices that help regulate the autonomic nervous system and support the strength of the vagus nerve (vagal tone). These practices work best when done slowly, regularly and in a way that feels supportive rather than effortful.

Softening the breath

Gentle, slower exhalations support the parasympathetic system and help your body settle.

Try it:

- Inhale softly through your nose for a count of 3 or 4.

- Exhale through the nose or mouth for a count that is slightly longer; 5 or 6, or even up to 8.

- Repeat for 6–10 rounds, focusing on the sensations and sounds of breathing in your body.

Orienting

Letting the eyes move gently through your environment helps your system register safety and presence.

Try it:

- Let your eyes slowly look around the space where you are.

- Notice colours, textures, shapes or pockets of light that feel neutral or pleasant.

- Take a soft breath when you find something grounding, letting your system register “I am here.”

Grounding through sensation

Feeling the weight and contact of your body helps orient you to the present moment and reduce internal activation.

Try it:

- Place both feet on the floor or let your body rest into the support beneath you.

- Notice points of contact; pressure, warmth or stability.

- Let your attention stay there for a few breaths, without trying to change anything.

Soothing touch

Warm, gentle touch communicates safety through sensory pathways connected to the vagus nerve and helps muscles release unnecessary tension.

Try it:

- Place a hand on your heart, belly, upper arms or any area that feels comforting.

- Apply gentle, steady pressure or small circles of soothing touch.

- Add a soft phrase if helpful, such as “I am here with you” or “We can go slowly.”

Mindful movement

Slow, simple movements invite muscles out of bracing and help discharge low-level survival energy.

Try it:

- Choose a small movement: rolling shoulders, circling wrists, stretching your spine or gently swaying.

- Move at half your usual speed, paying attention to sensation rather than performance.

- Pause occasionally and feel the after-effects in your body before moving again.

The link between safety and connection

Safety and connection are inseparable. When you feel safe, you can connect with other people; and when you connect with safe people, you feel safer. This is why co-regulation is one of the most powerful somatic tools we have.

Connection can come from relationships, but also from nature, animals, spiritual practices or supportive objects such as blankets or scents. Anything that communicates steadiness to your system offers co-regulation.

Creating daily safety rituals

Small, predictable rituals help your nervous system feel anchored. These rituals become cues of safety that accumulate over time. Why not try to incorporate some little safety rituals into your day? Here are some ideas to weave ritual into your life:

- Morning orienting; looking around at your environment to confirm where you woke up is a safe space.

- Try co-regulating with yourself: say "good morning, Claire/your name" either with a hand on your heart or to your reflection in the mirror.

- Try 2–3 minutes of deep belly breathing after waking up or as you wind down before bed: In through the nose into the belly to relax the diaphragm and slowly out again through the nose or mouth.

- Explore creating consistent sleep and wake times and tie these in with your little rituals in the morning or evening like orienting or belly breathing. The nervous system finds safety in familiar patterns and predictability.

- Using sensory cues such as warm drinks, soft lighting or comfortable textures.

- Take a few minutes to practice singing, chanting or humming - which all activate the vagus nerve.

- Try slowing down and really noticing your food for one meal or snack a day. Put away distractions and focus on the experience (smell, taste, sensations). This sends signals to your brain that there is no rush and it is safe to slow down.

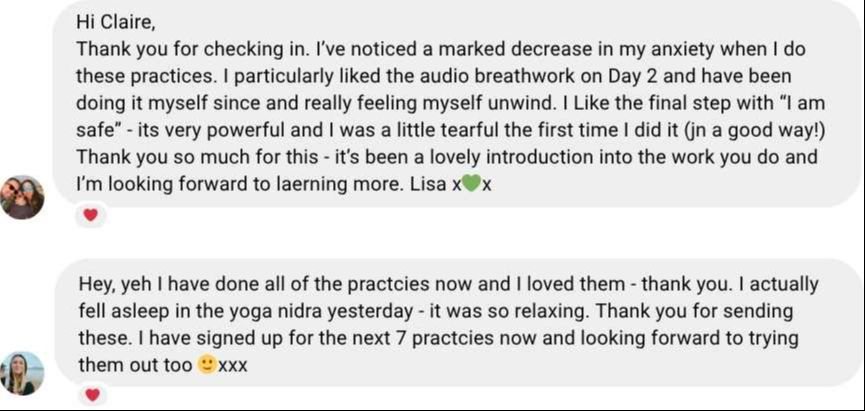

Somatic Self Healing and felt-safety training

Felt safety is at the heart of Somatic Self Healing. Throughout the programme, you learn to:

- understand the physiology of safety and protection

- rebuild your connection with your body

- practise daily somatic tools

- process past protective responses gently and safely

- strengthen your capacity for grounded, embodied presence

The more your system experiences safety, the more it trusts it. Over time, these practices become second nature and your body begins to feel like home again.

Want gentle support feeling safer in your body?

Join my Free 5 Days of Somatic Practice: a series of micro-practices designed to support nervous-system safety and help you reconnect with your body.

Join free todayReferences

Dana, D. (2018) The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation. New York: W. W. Norton.

Levine, P. A. (1997) Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Maté, G. (2003) When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress. Toronto: Vintage Canada.

Ogden, P., Minton, K. and Pain, C. (2006) Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. New York: W. W. Norton.

Porges, S. W. (2011) The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. New York: W. W. Norton.

Schwartz, R. C. (1995) Internal Family Systems Therapy. New York: Guilford Press.